This is Part 4 of a five-part series on the effects of Covid lockdowns on children and education. Part 1 can be found here, Part 2 is here, and Part 3 is here. The purposes of the series are to:

- Present the evidence of what has been done to our children — a compendium to remind people of the damage inflicted on a generation and for which no one has been held accountable.

- Reject lockdowns as a valid public health strategy.

- Reflect on the experiences, words, and feelings of the children and those trying to educate and care for them, and

- Highlight that, in the words of Professor Ian Brighthope, “They knew. They did it anyway”.

Part 3 set out the feelings and experiences of the children and their parents. But what about those who were trying to educate and care for them?

Part 4 sets out their feelings and experiences. By way of introduction, this article opens with a reminder of the children’s experiences to set the scene.

As Chris Quinn, the Northern Ireland Children’s Commissioner said as he was expressing the feelings of a mother, “One of her children was afraid to let Santa Claus into the house during the pandemic”. And, in the words of a five-year-old, “I don’t need anybody to play. I am used to being lonely”.

Monye Anyadike Danes KC, representing the Northern Ireland Children’s Commissioner in her final closing statements to the Scottish Covid Inquiry, gives a voice to those children: “We, the children, realise that we were simply not considered individually or as a group”.

They weren’t. The Spectator reported that in Professor Neil Ferguson’s testimony to the Covid Inquiry, Ferguson, the architect of many lockdown models, stated that the side effects of lockdowns, such as damage to education, were not considered “because the government didn’t ask about them [emphasis added]”. Helen MacNamara, former Deputy Cabinet Secretary, spelt it out: “ There wasn't enough thinking about the overall experience of children who might not have quite the same privileges as the people who are in rooms in Whitehall making decisions”.

As previously reported, a study by University College London found that “Children were forgotten by policymakers during Covid lockdowns”. The study found that politicians did not consider children and young people a “priority group” when English lockdowns were enforced. Further evidence was provided by Robert Halfon, Chairman of the House of Commons Education Select Committee. Speaking in August 2022, he stated, “What is frightening is that there was very little consideration given to the disadvantage that pupils would face from school closures”.

And this lack of consideration led to the absence of appropriate Children’s Rights Impact Assessments, no acknowledgement of children’s rights, and insufficient attention to a child’s best interests, as highlighted by the Scottish Children’s Commissioner, Nicola Killean.

Monye Anyadike-Danes KC, who represented the Northern Ireland Children’s Commissioner at the Inquiry, spoke chillingly about what happened:

It was recognised that government policies and measures were knowingly causing huge harm to children and young people and that they were paying a huge price to protect the rest of society. There has been no proper explanation for such an egregious failing … to have recognised that you are intentionally doing something likely to cause harm …recognise that it is causing harm and yet not having done the work to put in to mitigation or a reduction in those harms is simply inexplicable and has not been explained … No one has taken responsibility, or is likely to be held accountable, for the harm inflicted on them, which in many cases was intentional, knowing it would cause harm.

The Feelings and Experiences of Those Trying to Educate and Care for Children

The purpose of this article is to give voice to those who are trying to educate and care for children. To understand their feelings and experiences, I conducted primary and secondary research. The main method was by means of a questionnaire, after which there were follow-up interviews by telephone and messaging. I also wanted to assess whether experiences differed according to the type of school, the seniority of the teacher and the role played by the person in children’s education and well-being.

I contacted parents with children in primary school, in secondary school, at university, and with special needs. I contacted a range of educators, including teachers in nursery schools, primary schools, and selective and non-selective post-primary schools, classroom support teachers, university lecturers, and psychologists. I also contacted a range of teachers with varying degrees of experience, including headteachers.

As a Director of the Northern Ireland Council for Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment, I was aware of the concerns, experiences and feelings of a large group of educationalists, including teachers, headteachers, unions and churches through written and oral reports.

Their responses are presented verbatim. Secondary research has been included to provide specific information, such as the impact on education and speech and language development.

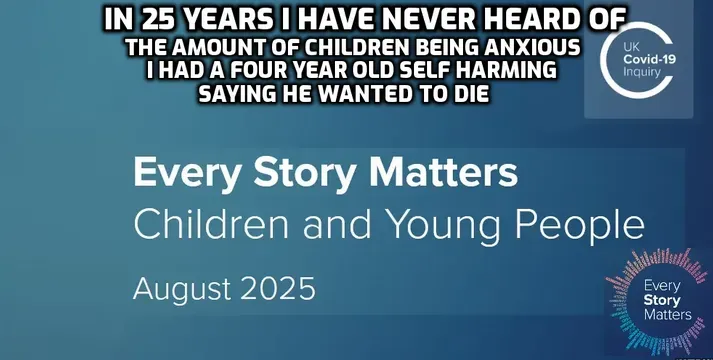

My haunting fears for children and young people grew exponentially by the day after the first lockdown was announced. Working therapeutically within the fields of attachment, trauma, abuse and neglect, I could hardly bear to imagine what would be going on in millions of households around the country. Isolated at home, callously abandoned by the institutions that oversee their welfare, locked in with abusive and/or stressed-out parents. Other nightmare scenarios followed. Mothers having babies in dystopian environments with no aftercare. Toddlers are being looked after day in, day out by terrified masked-up parents/carers. Attending school while wearing masks for 8 hours a day and being denied social and extracurricular activities. Invasive testing, sanitising, and vaccinating.

I watched and witnessed it all with a growing sense of horror and isolation from most of my peers, friends, and professional organisations. My fellow human beings are turning into robotic, fearful, face-covering cowards, putting their safety ahead of children, using them as human shields. I witnessed the fallout in my therapy room – mothers unable to bond with their babies, teenagers wearing masks long after it was ‘mandated’ to hide their self-consciousness, traumatised adopted children receiving no vital support from professionals cowering behind screens at home. Children and young people are missing, suicidal, self-harming, and let down by those meant to protect them, and the list goes on. With no collective healing or recognition of the trauma, this list of inexcusable harms is destined to fester and grow. Shame on everyone who allowed this to happen.

— Sarah Waters, a certified psychotherapist and therapeutic parenting practitioner

It was traumatic for the school and pupils during lockdown and post-lockdown. They credit me with keeping the school open when so many staff are forcibly off. I was one of the few who would go in … as well as the academic loss it was much more the soft shills which were damaged, the development of friendships, coping mechanisms, all the natural landmarks in child development etc, speaking to people in industry, there has been a big post covid effect on the work force and, in particular, apprentices … no one knows how to work anymore!

Teaching is such a form of personal relationships, trust, respect, care, admiration and leadership. When discussing volcanoes, no computer can replace me telling the class the sheer awe I experienced after visiting Pompeii and then standing on the crater rim … nor passing around the piece of porous volcanic rock I brought back as a souvenir!

Some boys thought it was acceptable because they could stay at home; they didn’t have to go outside, which enabled them to remain firmly within their bubbles and thus not “working through” the usual teenage developmental stages. Some girls preferred being at home, but the more conscientious students missed teacher feedback; others found the unreliability of distance learning stressful, both materially and emotionally. Pupils now do not really like going outside.

— Ian, a teacher with 45 years of experience

I worked at a public school during the pandemic, in a U.S. state that didn’t have the drastic closures (such as California), and it was still horrible. The end of the 2019-2020 school year was moved online, with all the kids’ activities and celebrations cancelled. For seniors, this meant once-in-a-lifetime events such as choir trips, Prom, and graduation were opportunities lost forever. Coming back in the fall of 2020, there was a red line down the middle of all the halls to direct single-file traffic. It felt like a prison, with no talking or interaction allowed, and everyone’s faces covered by mandatory masks. Every day, administrators actually measured six feet away from the desk of anyone who had tested positive for COVID the day before, and all those children and teachers had to quarantine for days, even if asymptomatic. Teaching was completely disrupted due to Covid measures. Students and teachers were treated like behaviour problems if they didn’t wear masks. There were PVC pipes and plastic partitions set up in the lunchroom, dividing the tables into small cubicles of isolation for each student. Choir, band, dance, and gym classes were severely hampered by masking, social distancing, and the elimination of much of what these classes typically entailed. Drinking fountains were roped off. Faculty were not allowed to gather in the Faculty Room at lunchtime or at any other time. There were no school plays that year. The custodians were placed under a heavy burden of sanitising every surface in the school each day in addition to their regular work, and substantial funds were spent on unnecessary hand sanitiser and other products. Plastic barriers went up in all the offices and around most teachers’ desks. When sports teams resumed, Covid testing and masking were required for months, limiting breathing and subjecting students to invasive nose swabs. In short, the school environment was co-opted by the Covid fanatics, to the complete detriment of the students. We are seeing the fallout today, at the middle school where I work, with behavior problems, lowered test scores, socialization issues, and high numbers of students with anxiety and depression.

Watching adults panic and allow the world to crumble around children first caused me great incredulity. Surely the cooler heads among parents, educators, religious leaders, elected officials, and the discerning voices in the media and medical community will put a stop to this insanity, I thought. But they didn’t, which led to a burning anger and frustration, and a determination to fight my corner. I also felt fear and isolation, and like I was living in a dystopian novel or episode of the “Twilight Zone.” My response was a driving passion to research and write the truth, and to engage in outreach to decision-makers and anyone who would listen.

Great harms were perpetrated on the defenceless and weak throughout the world, in the name of Safety and Public Health, and are ongoing today. By turns, I’m angry, discouraged, incredulous, and sad as I observe that there has been almost no reckoning or truth-telling on the part of the perpetrators of the poisonous pandemic response. Also, I’m surrounded by vaccine-injured people, many of whom don’t know that the COVID shot is what led to the demise of their physical health. That is also a huge sorrow. Thankfully, we Covid dissidents throughout the world eventually found each other, despite the censorship and attempts to silence us, which has given me a community and hope.

— Lori Weintz, a classroom support assistant

The most heart-breaking moments involved those who used the mask to hide behind, grew their hair (so you could hardly see their faces), and withdrew completely into themselves. Others didn’t have a chance to establish friendships before lockdown, and those who didn’t have phones/fellow pupils nearby came back to school lost. It was awful being expected to tell pupils to wear masks all day when teachers didn’t. I told them they could take them off, and my own child didn’t wear one. I told them they didn’t have to take the COVID-19 tests home, too. I resented being asked to give them out.

— Kiera, a senior teacher

Remote learning was promoted as an equal learning experience, but my experience was totally different. Pupils turned off their cameras during live online lessons. Many didn’t attend. [It was] hard to have any meaningful interaction. [It was] very stressful to schedule/teach from home. Pupils also struggled with finding a quiet space. Some teachers reported poor behaviour online.

In addition, I had no ability to care pastorally. It would have been inappropriate to email individual pupils to ask how they were. When some returned, they were visibly and psychologically changed. They often withdrew. Boys in particular hadn’t had time to establish friendships at a new school. Those in rural settings were very isolated. A pupil wrote an essay about being made to self-isolate in her room ‘for the greater good’.

I was very frustrated, stressed and upset. Trying to juggle teaching other people’s kids and my own was mentally exhausting. Knowing that pupils weren’t doing enough meaningful work was frustrating. Had to make a timetable for using the kitchen in my house. Not appropriate to teach children from bedroom setting. Difficult to mark/correct work online using an iPad. Parents would complain when pupils got a poor report/exam grade, but if they didn’t engage, then we couldn’t make up a mark for them. Missed the spontaneous nature of the classroom.

The policy of sending children home when they tested positive had a serious effect on me, all negative. [I was] often left with a handful of pupils in class. Having to measure those within 2m was disastrous.

The whole experience was awful. The first lockdown wasn’t so bad, but pupils got a poor service: one email on a Monday with the week’s work. Second lockdown: terrible. Trying to juggle learning the technology to deliver lessons online was hard. Return to school with masks: rotten. Oppressive/harmful. They had a terrible psychological effect on some pupils who used them to withdraw into themselves. Staff became afraid of the pupils in their classes and obsessed with windows being open. Some are still opening every window and freezing the pupils (watching the CO2 monitors obsessively). Making school ‘optional’ has led to high absence rates and more dropping out. So many pupils missed school because they had a cold. Staff absence levels increased. We were asked to declare if unvaccinated to the principal (as we’d have to self-isolate for longer). We didn’t tell. Led to climate of fear and suspicion among staff.

— Aoife, a senior teacher

If one parent panics and puts their poor child through that horrendous test, it causes havoc with hundreds of families. My granddaughter has been sent home for two weeks due to one classmate testing positive. She cannot attend her hockey practice, her gym classes, see friends or even visit the local park! She has become sullen, withdrawn and tearful. The stress on families juggling work commitments is terrible.

— A carer

We had no technology in school capable of the video making that I decided on, so school was essentially run from my iPhone 6 (what I had at the time) and a school laptop.

Very conscious that families probably don’t have the resources available in school, and that there are cost implications for many activities.

Very stressful at the start — and very time-consuming — as I grappled with unfamiliar technologies and tried to find ways around challenges like FB becoming very difficult, getting videos uploaded and scheduled. It just felt like I was constantly struggling and working very long hours.

My biggest worry was those children on the Child Protection register, as I obviously didn’t have daily sight of them. There was better guidance in the second lockdown.

My other big worry was the SEN children — both those with a statement who weren’t getting the support they needed and those I was in the process of identifying and getting them through the statementing process.

I ended up providing a bedtime story online seven days a week, as it was the glue holding one family together. I felt a responsibility towards them when mum told me on day three that she used that to structure the child’s day.

I was also concerned about a couple of families where the mums were struggling with mental health. Fortunately, they engaged (lots!!!) with me – but again I felt the need to be available to them.

How did I feel? Worried, anxious, unsupported, very stupid when I didn’t know the technologies and had to struggle to find out how to do things, a sense of personal responsibility for my children in school, and for my staff.

The sense of fear that surrounded us all was so stressful.

It was so difficult to switch off – I found myself responding to emails and messages well into the evening – but I did set parameters in the second lockdown.

I began to try to see the positives in that what I was doing seemed to be working reasonably well, especially the feedback and engagement from parents.

I began to try to see the opportunities – some things we had to do to get school reopened were things we would have liked to do previously, but didn’t feel that we could. They worked – with the efforts of staff and cooperation of parents – and we continue with them.

I learnt to innovate and developed tech skills I didn’t even know existed.

I suppose the last three points are more in retrospect, but I do try to see the positives in life.

However, I would never, ever want to go through it all again.

— Grace, a headteacher in a nursery/primary school

They are all so behind in their reading, writing, and number work, and they are lacking in emotional maturity, self-regulation of emotions, concentration span, and listening skills. As a literacy support teacher, it is beyond question that the lengthy lockdown periods and the requirement to quarantine disadvantaged a significant percentage of children with special needs. Their rate of progress was clearly affected by the policies. I constantly feel hurt, sad and frustrated for children who are struggling due to the breaks in their teaching and the resulting slow rate of recovery. The added pressure on classroom teachers due to children not having caught up is clearly reflected in liaison meetings.

— Margaret, a teacher with 30 years of experience with special neeeds children and in the primary and nursery sector, comparing her current cohort with previous cohorts

A growing number of young children in Northern Ireland are experiencing significant communication problems following the COVID-19 lockdowns. We’re seeing children who can’t talk at all; they grunt or point at things they want. They don’t know how to speak to the other children, and if they want a toy, they will push the other child out of the way or snatch a toy from them. We’re seeing more children who can’t sort shapes or do three or four-piece jigsaws.

There are also children who become distressed because they can’t communicate, either because they can’t understand what is being said to them or because they can’t express themselves. They would have been about 2 years old or younger at the start of the pandemic and have spent half their lives during it, so it has really impacted them.

— Ruth Sedgewick, Head of the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT), Northern Ireland

At the Scottish Covid Inquiry, Nichola Killean reported that children with additional needs, such as children with disabilities, had no access to services and support. This was also emphasised at the Inquiry by Rhona Black (Head of Nursery and Kindergarten, Kelvinbridge), Karen Flynn (Director, Kirktonholm Childcare), and Ross Keenan (Director, Cosmic Coppers Childcare), who are all operators of privately independent nurseries and members of Early Years Scotland. Mr Keenan testified,

We had to not only isolate the children and staff, but we had to find spaces in nurseries that were able to be segregated to keep the children and staff in their own separate bubbles and to purchase two outdoor classrooms, 2.4-meter-high Perspex sheets, and 'traffic lights' to accommodate bubbles and 16 children in the garden in probably one of the coldest winters. During the transition process, we were taking babies out of their parents' arms at the doors. It’s very obvious that the children have lost a lot of experience and understanding of social interactions. Lots of children hadn’t been anywhere other than within the four walls of their own homes.

With respect to support services, he added:

The most vulnerable children were abandoned. All in the name of public health. The biggest adverse impacts were on those with additional support needs. There was nothing to speak of in terms of any support for the kids, the support we had pre Covid almost disappeared … there was no support.

He also referred to the impact on staff of isolating children and staff, and of keeping children and staff in separate bubbles.

Staff were ‘all gowned up’ and stood against a wall in the playroom, terrified of contracting Covid from young kids. Mental health issues hit the staff, and they really began to crumble.

Education requires an atmosphere conducive to learning. Learning cannot take place in an atmosphere of fear and anxiety. Teaching and learning require unimpeded visual and oral communication. Good teaching involves a variety of strategies that take into account pupils' different learning styles. It involves interactivity, group work, teamwork, discussion, and detailed complex explanations. Imagine a question-and-answer session, a drama lesson, a language lesson, a poetry reading, a role-play session, or a singing lesson when children are at home or wearing masks.

For many children, school is the only stable and secure part of their lives, offering the vital pastoral and counselling work that identifies and supports children in crisis. When pupils are out of school, the most vulnerable are the most affected; teachers can’t pick up the early warning signs of abuse or neglect, and children have no one they can tell.

Sport and extracurricular activities are important in children’s lives. Events such as school plays, school trips, choirs, and the first and last days at school mark out their lives and are vital for their social development. Friendships are crucial for their emotional development, particularly during the critical stages of growth – childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood – and especially when there are vulnerabilities or special needs. Children need access to family, friends, services, and support.

The development of leadership, teamwork and negotiation skills are enhanced through children’s participation. Socialisation is a vital aspect of education; young children learn to share, help others, and appreciate differences whilst in school. The insight gained by watching children participate in a range of activities enables teachers to recognise and value attributes such as commitment, leadership, and reliability.

What saddened me was that children lost all those once-in-a-lifetime events which can bring such richness to school and their lives, the excitement of the first day, the ski trip, playing for the school, the leavers’ fair, the drama production, and the satisfaction of passing exams.

What angered me was the inability to help children over the vital reading threshold into functional literacy and the lifetime consequences for them. The standard reading regression that teachers expect every year, caused by the transition from primary to secondary school, has increased substantially. How much of this regression can be reclaimed in the current disrupted schooling system is unknown, and the downstream effects on our children could be disastrous.

Important engagements with outside agents such as authors, sports coaches, careers officers, counsellors, translators, actors and artists were clearly not possible when schools were closed, or children were isolated at home.

Children with special educational needs require personal contact with their teachers. For many, facial expressions provide reinforcement, and these visual clues are vital. Children on the autism spectrum need to be able to recognise facial expressions as part of their ongoing development. Teachers often assess the extent of their pupils’ understanding of their teaching from pupils' facial expressions. Expressions are essential for gauging emotions and for teachers to detect nonverbal communication related to deep feelings. For children with special needs, essential access to multi-agency support frequently ceased. Clearly, so-called remote learning does not work for these children.

In my view, denying children and young people the activities that nurture their well-being and mental health, such as school, sport, travel, church, and parties, has had inevitable consequences, as evidenced by the rising tide of young people seeking help. In addition, the media and government conducted a highly emotional campaign to frighten them, seemingly without any consideration for the short- or long-term effects.

When schools did re-open, they did so in a phased manner and under strict conditions. This placed immense stress on Principals and school leaders who had to reassure children, parents and staff whilst at the same time organising staff rotas, part-class rotas, year-group rotas, timetable changes, staffing, desks, movements, toilets, meal times and teaching.

As a Director of the Northern Ireland Council for Curriculum, Examination and Assessment, I witnessed firsthand the stress placed on officials as they wrestled with the task of providing vital GCSE and A-level examinations when schools were closed. Issues relating to coursework, orals, practical examinations, and modular examinations, and which sections of the curriculum could be omitted from the examination itself, weighed heavily on those charged with ensuring that our young people were not further disadvantaged.

The implications of lost learning at high-stakes boundaries are clear; the exam board OCR reports that nearly a third of GCSE and A-level students have lost more than 50% of their learning time, with some losing 100%. Pupils who miss out on basic GCSE passes, in English or Maths, for example, may forfeit a job opportunity or fail to secure a sixth form place. Students dropping an A-level grade may miss out on a university place, consigning teenagers to comparatively inferior employment and earnings prospects for years. There was particular concern about those children in the grade C-D-E boundary area. These children would almost certainly have benefited from robust in-class teaching in the vital months leading up to exams.

Sixth-form students faced an uncertain future and expressed concerns about how they would be assessed. They questioned the wisdom of going to university with no face-to-face teaching, paying hefty fees, and possibly locked in their halls. And, if so, what are the implications?

Then there was the added uncertainty of how their grades would be perceived. Universities and employers might have been sceptical about how grades translate into suitability for university entry or employment.

How will the absence of practical experience be made up, for example? a medical professional in training, a recently graduated engineer, or an apprentice electrician.

A further concern was the portability of examination qualifications. For Northern Ireland, our examinations and grades must be equivalent to England’s in order to ensure Northern Ireland children have access to English universities.

As a Director of the Board responsible for the decision-making, I certainly felt the stress and the weight of the complexity and importance of the decisions.

I found no difference in the views of educationalists across sectors or with differing experience; rather, their views and their willingness to express them depended on whether they viewed Covid as deadly and the policies justifiable. It is telling that many preferred their feelings to be recorded anonymously, and for this reason, their names have been changed.

Was All This Necessary? The Justification for School Closures

The reason given for closing schools was to protect children and prevent them from transmitting the virus to other family members. The evidence says something different. Extensive research published by NIH, found “not a single instance of a child infecting parents”.

In September 2020, Public Health England had reported:

We found very few infections and transmission events in 131 educational settings during the 4-6 week summer half-term from 1 June to mid-July 2020 2. Where a SARS-CoV-2 positive case was identified, we did not find any additional cases within the household, class bubble or wider education setting when tested.

In addition, according to Professor Ioannidis, children have a 99.9997% chance of survival, yet we continue to restrict their lives.

The idea that virtual or ‘remote’ learning was an adequate substitute for in-person teaching was promoted by the government and used to justify the extension of school closures. This issue is explored in Part 5; a brief commentary on the outcomes is provided below.

The education and mental health data from around the world tell their own story, as does the decline in the performance of UK schools, as measured by international academic tables, a “shocking indictment of the way education was sacrificed” during the Covid pandemic, as The Telegraph reported. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) registered a sharp decline in 2023. The Pisa tests compare educational attainment among 15-year-olds around the world and show UK schoolchildren achieved their lowest scores in mathematics and science since 2006 — the first year of comparable data. Reading results were also down, close to the previous lowest score back in 2009.

The decline in the UK is mirrored across the developed world. The evidence from the US was particularly clear: “… a consistent trend was evident from 2011 to 2019, and then a significant decline in 2020 and 2021, corresponding to the COVID-19 pandemic”. The mean Early Learning Composite (ELC) developmental score dropped by 20 points among children aged 3 months to 3 years. Additionally, “Children born during the pandemic have significantly reduced verbal, motor, and overall cognitive performance compared to children born pre-pandemic”.

A finding confirmed by a study in JAMA Pediatrics found that “compared with the historical cohort, infants born during the pandemic had significantly lower scores on gross motor, fine motor, and personal-social skills”.

BiologyPhenom quoted Baroness Hallett’s closing remarks: “And that completes the oral hearings for Module 8, the devastating impact of the Covid pandemic on children and young people”.

But, as BiologyPhenom rightly pointed out,

As the evidence at the inquiry reveals, it wasn’t any pandemic of a novel virus harming children en mass [sic] it was the destructive human rights-depriving lockdown measures implemented from March 2020 [emphasis added], along with associated media scaremongering. These were the real assaults taking place upon millions of lives.

BiologyPhenom also provided an excellent compilation of children’s experiences due to government policies.

As Professor Russell Viner, President of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), told the Education Committee at Westminster in January 2021: “When we close schools, we close [young people’s] lives, not to benefit them but to benefit the rest of society. They reap the harm when we close schools”.

Monye Anyadike Danes KC, in her final closing statements to the Scottish Covid Inquiry, asked, “What coordinated work has been done by the government to identify the full impact on them, and what is now in place to help them?” She goes on to answer her own question:

There are no coordinated activities to identify and tackle the range of impacts on children and young people. There doesn’t appear to be the data to determine who has been harmed and how, and without that, it is difficult to see how there can be effective recovery plans to help them.

And, referencing the children, she added:

The approach taken has led to a diminution of respect for education and schooling in N. Ireland. Hope can be found. It is my wish that steps can be taken immediately and robustly to assess the impacts of Covid on all young people to attempt to mitigate against the damage they have done. Our voices need to be represented.

Sadly, it doesn’t seem that there have been any lessons learned now or for the future. Here, Danes refers to Derek Baker’s written statement: “no formal exercises have been commissioned”. Baker was then Northern Ireland's Permanent Secretary at the Department of Education.

I will close with Danes' telling statement, quoted earlier in the article: “No one has taken responsibility or is likely to be held accountable for the harm inflicted on them [the children], which in many cases was intentional harm, knowing that it would cause harm”.

Why?

Part 5 of this series, co-authored by myself and Professor Diane Rasmussen, UK Column’s Commissioning Editor for Written Content, will present experiences of teaching and learning in the higher education sector during the Covid lockdown era. It will also explore the pedagogy of remote/online learning (does it exist?) and question whether it worked.