This is Part 3 of a four-part series about the effects of Covid lockdowns on children and education. Part 1 can be found here, and Part 2 is here. The purposes of this series are to:

- Present the evidence of what has been done to our children; a compendium to remind people of the damage inflicted on a generation and for which no one has been held accountable.

- Reject lockdowns as a valid public health strategy.

- Reflect on the experiences, words, and feelings of the children and those trying to educate and care for them.

- Highlight that, in the words of Professor Ian Brighthope, “They knew. They did it anyway”.

This article focuses on the damage to children and recounts the experiences, words, and feelings of children and their parents. As Martin Luther King said, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy”.

The UK Covid-19 Inquiry, the Government’s official review of how the nation handled the so-called pandemic, has allowed us to see where the men in charge stood. As the Inquiry drew to a close, the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Professor Chris Whitty and the then-Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, gave their accounts.

Whitty told the Inquiry that he “couldn’t see the logic” of making people stay home so much, and went on to refer to the harms inflicted on isolated children:

I couldn't see the logic of that from an infection control point of view, to be honest. I think it almost happened by accident, and that's probably something we should have looked at. And for children in particular, I think that's very important. It's pretty obvious that having children isolated is not a natural situation and is not good for children. The scientific evidence supports what common sense would tell people. These are things you would not wish to do to children. I'm completely sympathetic to the view that children’s play is essential to children.

The CMO then said that school closures “could have been done better”.

Boris Johnson told the Inquiry that he believes Covid rules went “too far” for children, and they paid the price:

I think that looking back on it all, the whole lockdowns, the intricacy of the rules, the rule of six, the complexity, particularly for children, I think we probably did go too far. Don’t forget, we didn’t know the effect this disease had on kids. We didn’t know much about the transmissibility of the disease.

This article serves as a commentary on the CMO’s and the Prime Minister’s testimonies. Professors Heneghan and Jefferson call them “the shameless performance of Sir Christopher and Mr Johnson”. They go on to say how they have tried to hold:

The powerful accountable for the catastrophe and its aftermath. For the use of soothsayers and sundry charlatans to frighten and bully a freeborn people, for the lies and reckless waste of resources.

And ultimately for the useless Hallett Inquiry, which is forecast to cost £200-208 million by its conclusion (that is, if it ends in 2027).

Why do I qualify it as useless? Because, to my knowledge, no one in a position of power was asked the million-dollar question: ‘What was the evidence you based your decisions on?’

This series presents the evidence available to “soothsayers and sundry charlatans” at the time, and, of course, part of the purpose is to hold those responsible for “the catastrophe and its aftermath” accountable for their actions and to add to the body of evidence highlighting the damage and futility of school closures so that they never happen again.

In fact, despite what the former Prime Minister stated, they did know “much about the transmissibility of the disease” and the risks to children, as is made clear in this revealing disclosure by Whitty in August 2020: “Children are more likely to be harmed by not returning to school than if they catch Covid”.

And in the same month, it was revealed that children do not transmit the virus. Professor Mark Woolhouse, a member of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), said in an August 2020 Daily Mail article:

There are thousands and thousands of transmission events that have been inferred [from contact tracing]—out of all those thousands, still, we can’t find a single one involving a child transmitting to a teacher in a classroom.

In fact, SAGE itself had concluded by December 2020 that transmission in schools, when open, was no greater than transmission anywhere else in society, so school closures were doing nothing meaningful to bring down transmission rates.

Shamez Ladhani of Public Health England revealed that “they aren’t taking it home and transferring it to the community, kids have very little capacity to infect household members”. This was confirmed by a study reported in The Times in August 2020 under the headline ‘Children Are Unlikely To Be the Main Drivers of the COVID‐19 Pandemic’.

In addition, the European equivalent of the powerful American Centres for Disease Control (CDC), the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), reported in August 2020 that children were much less likely to contract the virus. It noted that “re-opening schools has not [emphasis added] been associated with significant increases in community transmission”.

And the risk to children? This was the alleged justification for school closures.

According to research published by the US Government’s National Institutes for Health, for children aged 5–11 years without co-morbidities, the case fatality rate could not be calculated due to an absence of cases.

So, just to be clear, we have the PM saying the Government didn’t know the effect this disease had on children, nor much about its transmissibility, and yet the Government’s agencies stated they did.

The CMO made this astonishing statement when referring to making people stay at home: “I couldn't see the logic of that from an infection control point of view, to be honest. I think it almost happened by accident and that that's probably something we should have looked at”.

So they certainly would have known by November 2020 when a second lockdown was ordered. There was a third lockdown in 2021, as was set out in Parts 1 and 2 of this series.

In this context, the comments by the King’s Counsel (KC) for Module 8 of the Inquiry, Clair Dobbin, that whilst school closures and lockdowns, though enormously damaging, “might nonetheless be needed in the future”, provide an additional reason why evidence exposing the futility and harms of lockdowns and school closures must continue to be presented.

Part of the enormous damage to which the KC referred and which was also known, was contained in a Department for Education paper shown to Mr Johnson, warning that 1.3 million of the poorest children would not receive a free school meal, while remote learning would fail many kids. It also warned that the most vulnerable children are much safer in school, and that school closures would put many at risk of domestic violence or youth crime.

There is mounting evidence that missed learning and isolation during the pandemic have had a lasting developmental impact for some, as revealed in a series of UNICEF reports. Robert Jenkins, UNICEF’s Head of Education, said in 2022: “In March, we will mark two years of Covid-related disruptions to global education. Quite simply, we are looking at a nearly insurmountable scale of loss to children’s schooling”.

UNICEF itself reported that “the quantity of education lost is momentous”. At its peak, school closures affected 1.6 billion children in 188 countries. Classroom closures continue to affect more than 635 million children globally, with younger and more marginalised children facing the most significant loss in learning after almost two years of Covid. Another UNICEF report found that 150 million additional children will grow up in poverty. Millions of girls are being driven into child marriage, and over 80 million children are missing routine childhood vaccination for diseases that kill them. Lockdowns are estimated to be responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children — 228,000 in South Asia alone, according to another UNICEF report.

The World Health Organisation reported that over 60,000 additional children died from malaria in 2020 alone, and it attributed this to Covid-related medical services disruption.

A summary of the devastation to education and young people provides a sobering testimony.

Of course, it is self-evident that if children are not at school, their education, development, and mental health will suffer. A series of reports had highlighted the issue.

As early as March 2021, the then-Children’s Commissioner for England and Wales, Anne Longfield, reported that the class of 2021 had lost the equivalent of 840 million school days. In July 2021, the BBC reported that in England at the time, almost a quarter of primary pupils and nearly a third of secondary pupils were absent from school, or 1.7 million children, of whom fewer than 3% actually had Covid.

On 9 March 2022, the BBC reported that almost two million pupils were regularly missing school. On 16 November 2022, The Telegraph reported that one-fifth of pupils are “missing” from classrooms since the pandemic, quoting a study by the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ). This included 1.67 million children classified by the Department for Education (DfE) as “persistently absent” during the autumn term of 2021, an increase of 82 per cent from the previous year.

And worse, the current Children's Commissioner in England, Dame Rachel de Souza said, “thousands of pupils left school during lockdowns and never came back”.

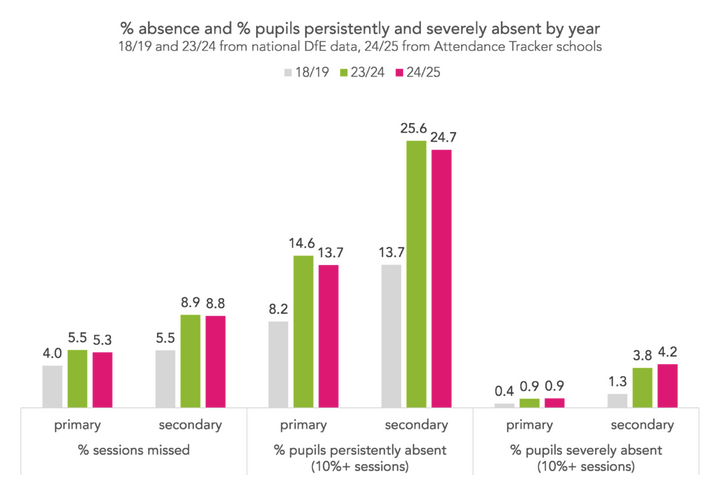

Indeed, as the up-to-date figures show, there are 3,671,427 pupils in state-funded secondary schools and 4,554,974 in state-funded primary schools, according to the Department for Education (DfE). The number of pupils absent from school remains “stubbornly high” and has not returned to pre-pandemic levels, according to DfE data.

Additionally, disadvantaged Year 7 students remain around twice as likely to miss school for any reason as non-disadvantaged Year 7 students, and around three times as likely to miss school for unauthorised reasons.

The Health Ethics and Advocacy Research Team (HART) also presents a comprehensive account of the harms to children.

The figures and reports, of course, hide the many untold personal and family traumas, the distress of the children, and the anguish and stress of their parents, some of whose stories will be told later in this article.

Western nations also saw a catastrophic decline in mental health, education, and development, with the World Bank highlighting the ongoing crisis. Last month, the World Bank warned that lockdown disruption to education would scar multiple generations of children who suffered severe developmental and learning delays.

The importance of early learning and the effects of primary school absence are clear. According to the Times Educational Commission, by the age of three, most of the brain (80%) is developed. By this age, most disadvantaged children are, on average, already more than 1.5 years behind their more affluent peers. By the age of five, 85 per cent of a child’s language is in place. This is the age at which many children are first introduced to the English language at school.

So, if disadvantage sets in early, it tends to sink in deeply. A child’s development score at 22 months is an all-too-accurate predictor of where they will be educationally at age 26.

Some 40 per cent of the attainment gap seen at age 16 is already in place before those children even start school at age five.

So the seriousness of school closures is very apparent.

Professor Hill presents a very succinct timeline of developmental damage across age groups.

The Updated Position

A scoping review released in July 2025 tracking the outcomes among young children growing up during the pandemic period, aged between one and five, confirms the damage:

15 out of 17 studies showed negative associations between the pandemic and developmental domains (behaviour, communication, language, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving, emotional, and personal-social skills), as measured with the ASQ-3 and ASQ SE-2 (Ages and Stages Questionnaire).

Children born and raised during the Covid restrictions were behind in virtually every important developmental area. They were worse in terms of

- behaviour,

- communicating,

- learning languages,

- physical capabilities,

- problem solving,

- handling emotional situations, and

- growing their capability for social interaction.

Every study that used the ‘Ages and Stages’ questionnaire found that pandemic-era children fared worse than those born before the Covid shutdowns.

Among three to four-year-olds, those who should be approaching the start of traditional school showed even more pronounced effects:

Neurocognitive assessment using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) found that children born during the pandemic had significantly reduced verbal, motor, and overall cognitive performance compared to children born before the pandemic and these skills continued to decline incrementally across the population level as the pandemic progressed.

A similar finding was reported to the Scottish COVID-19 Inquiry by Rhona Black (Head of Nursery and Kindergarten, Kelvinbridge), Karen Flynn (Director, Kirktonholm Childcare) and Ross Keenan (Director, Cosmic Coppers Childcare-Glasgow), all of whom operate privately independent nurseries and are members of Early Years Scotland. They reported that they were required to:

… not only isolate the children and staff, but we also had to find spaces in nurseries that were able to be segregated to keep the children and staff in their own separate bubbles and to purchase two outdoor classrooms, 2.4-metre-high Perspex sheets, and 'traffic lights' to accommodate bubbles and 16 children in the garden in probably one of the coldest winters,

and during the transitioning process, we were taking babies off parents at the doors.

They reported on a similar list of adverse impacts on pre-school children, namely reduced:

- social and emotional development,

- motor skills,

- language and communication,

- personal skills,

- independence and confidence, and

- disruption to feeding, eating, and sleeping.

Sally Weale wrote in The Guardian on 30 January 2025:

Some children are starting reception school ‘unable to climb a staircase’ while others were arriving at school in nappies — one in four who began reception last September were not toilet trained — teachers reported children with poor basic motor skills and underdeveloped muscles, which they linked with excessive screen use — a parallel survey said they thought children starting school should know how to use books correctly, turning the pages rather than swiping or tapping as if using an electronic device.

On 24 June 2022, Harriet Sergeant stated in The Daily Mail:

Dummies were the preserve of infants who would be weaned off them during the toddler years. But now they, along with nappies, bottles and other paraphernalia of babyhood, talking like cartoon characters they binge-watch and unable to feed themselves, are increasingly a feature of the nation’s reception classes — and even beyond. It’s a vivid illustration of the disastrous impact the pandemic has had on the cohort of babies and young children born just before and during Covid — consequences only truly emerging as they enter education.

Through the Eyes of the Children and Their Parents

While classrooms sat empty, children were shut away in their bedrooms and denied all the activities which nurture their development and mental health. Our children are now asking why they were penalised, why they were denied education and sport, why they were not allowed to see friends, to travel, or go to university. Adults should be asking, too.

This section uses the words and experiences of the children, young people, and their families to show what has been done.

I asked a group of children what they missed out on most. They told me they wanted to know why they were denied those once-in-a-lifetime experiences that they will never have, such as participating in educational visits, starting the first year at secondary school, playing sport for the school, being in a drama production, singing in the choir, passing an exam, attending the last year at school, and joining Christmas parties.

For example, John [editor's note: all parents' and children's names have been anonymised] said, “We spent 12 years at school and never got to say goodbye. Who were we protecting? Who was protecting us? Who was looking after my health and well-being? Shut away in our bedrooms”.

Janice said, “I didn’t like being told that I might kill granny”.

Throughout 2020, 2021, and 2022, the evidence had emerged and, of course, parents live their children’s nightmare. As parent Liz said: “She won’t come out of her bedroom, she doesn’t want to meet anyone, she is crying all the time, and doesn’t understand why she can’t see her friends”.

Here is Steve’s [editor's note: al explanation of why his young daughter hid behind her mother’s coat as we passed on a footpath.

The problem is my daughter can't seem to articulate what the issues are. All we really know is that lockdown changed her, and not in a good way. Her circle of friends was drastically reduced during lockdown, when the schools closed, and she couldn't see people. She became withdrawn, seeing only one or two friends occasionally. Her sleep became messed up and still is now. She is only 14, and sometimes we can't get her up until mid-afternoon. Sometimes she gets up, chats to her Mum, goes back to sleep and wakes later only not to remember doing those things. She has become heavily reliant on her phone during lockdown, and that has been a problem, trying to limit usage, etc.

He continued:

It was the head of year meeting today (23 October 2025) for my girl and parents. I got her out of bed at 7:30am and dropped her to her mum, whereby she got into bed and refused to get out. Her mum went to the meeting alone. She’ll sleep all day now … worried about removing her phone in case it isolates her as I see her as vulnerable, but might be a road we have to go down to rule out any such self-harming behaviour.

Sally said:

My daughter was in P5 at the time. At one point, the school informed us that a child in her class had tested positive; therefore, all the children in that class were required to provide evidence of a negative test before they could attend school. The child who had tested positive, we were told, had no symptoms whatsoever. We refused to put our perfectly healthy 8-year-old daughter through a medical test. We explained this to the principal, and told him we felt it was unethical that they were assuming our healthy child was a risk to others, and were denying her an education unless she went through an invasive medical test. The farcical nature of the whole thing — the fact that the child in question was not actually ill — seemed to escape him. He did say the policy was coming from the governors, so we asked him to register a complaint with them. He did this, and later reported back to us that they were horrified at our 'aggressive stance'. At no point were we anything but calm and polite! Anyway, we didn't send our daughter to school that week. So she missed school for a week.

Sophie added:

Exactly the same thing happened with our children, who were then Year 9 and Year 10. I went straight to reception and said that they would not be testing and to show me the PHA regulations, which stated that they had to test before being allowed into school if someone in their class tested negative. Needless to say, our children didn't test and remained in school. On another note, our daughter developed an unhealthy obsession with exercise and food during lockdown (as a form of control, I think), and was bordering on anorexia — she's thankfully better now.

Joan shared:

As a mother of two young children during 2020, it is only on reflection that I realise just how much damage was done to the mental well-being of my children and how many important events they missed out on: birthday parties with their friends, church groups, and baby swimming. These are missed life experiences. We cannot recreate them.

My son, whose nursery days came to a complete halt, often cried tears of frustration as I tried to 'teach' him. I am not the one he thought of as a teacher; to him, I was his mother, so this role was confusing, I wasn't equipped to teach him properly. Not to mention, I was caring for a relatively new baby as well.

My baby daughter missed out on all of the major socialising that would have been so useful for her development. As she has grown, it has become even more evident to me that she would have benefited massively from social interaction with her peers. Learning how to share and interact with a sibling did not prepare her for what was to come when she was finally mixed in amongst her peers.

It is only with time that I realise how cruel, damaging, and completely unwarranted the 'lockdown years' were for our young.

According to Kelly:

My daughter struggled with not being around her peers; not seeing her friends or being able to go out affected her confidence and conversation skills.

I still had to work, so trying to do schoolwork with my daughter was a challenge. It led to a lot of high emotions as she was frustrated, and this led to anxiety about schoolwork, so we ceased doing it. This badly affected her progress. The lockdowns created fear and anxiety for my daughter. We are a very close-knit family, and she cried every day to see her extended family.

The school closures, in my opinion, fuelled the increase in the use of phones and tablets, with many children developing an addiction to them.

Mask wearing didn't affect her physically as she was in primary school at that time; however, it did have a psychological effect on her, especially when people were muttering or being vocal and aggressive towards us for not wearing masks. This created a hostile and intimidating environment for us, as I refused to wear one. She would regularly come home upset and anxious.

Also, she has a slight hearing difficulty and is a skilled lip-reader, so on the return to school and teachers wearing masks, this affected her confidence and her education as she was no longer able to lip-read.

My first granddaughter was born in December 2020. She had no exposure to people at home or in her immediate family wearing masks. She often cried and screamed if anyone wearing a mask attempted to approach her or talk to her.

And worse, I am a Health and Safety professional, so I knew the likelihood of the blue surgical masks or the homemade versions the TV recommended having any form of positive impact was minimal, if not non-existent.

Lynn shared:

During the Covid years, my five children were at crucial stages in their lives. My boys were 12, 14, and 15; my girls were 17 and 19. All different personalities, all at different educational and emotional points. And although each of them was affected differently, one truth is unavoidable: every single one of them lost something they can never get back.

As their mother, I feel the scale of that loss more sharply than they do. I don’t think they’ll truly understand what was taken from them until they’re older, perhaps when they have children of their own, and they look back at what they were made to endure.

My youngest boy, only 12 and in his first year of secondary school, now says he barely remembers that year at all. It simply ended in March. A whole stage of his education is missing.

His 14-year-old brother, introverted and technically minded, loved the first lockdown for all the wrong reasons: endless gaming, hours online, and no real schooling. Teachers tried, but there were hardly any live lessons; mostly, work was sent to be done alone in their bedrooms. Hurling, football training, and matches were cancelled. That was a huge loss, as those sports were their whole social outlet and a healthy pastime that kept them fit and happy. They slipped from being active boys to sedentary, screen-immersed teenagers.

The contrast between my older two boys, only 18 months apart, is stark. My eldest, at 14, was always reading books, absorbing vocabulary; my second boy was scrolling and gaming. Not because he chose badly, but because the Covid environment forced him into it. His literacy is nowhere near as good as his brother’s now.

When schools finally reopened, masking added yet another barrier. No child can learn properly when breathing is restricted, attention is fractured, and the body is exhausted, so that also compromised their learning and their ability to interact with teachers and fellow pupils. My eldest son never sat his GCSEs. his A-levels became his first ever state exams, and the stress for him doing those exams was enormous.

My eldest daughter had fought tooth and nail for her place at Oxford. Coming from a comprehensive school, she faced enormous disadvantage in Oxford University’s gruelling multi-day interview process, but through grit, intelligence and sheer perseverance, she won a place at New College, one of the proudest moments of my life. I waved her off in September 2019, a young woman taking flight, beginning her new adventure. Five months later, she was home again, her first year halted mid-flight. Her entire Oxford experience collapsed into a laptop on her bed. I still have a painful image in my mind: a young bird who has just left the nest, wings open, at last in flight, only for those wings to be suddenly clipped, sending her tumbling back to earth. That is what happened to her. She took off into her future, and then was slammed back into a dystopian half-life. She missed the balls, the parties, the traditions of the summer term, the memories students cherish for decades. Even in the second year, social life was confined and constrained within the college walls. She coped, but she suffered anxiety, and some of her friends became deeply depressed, even suicidal. They didn’t all connect their despair to the restrictions, but I think any mother can see the link.

My second daughter, 17 during the first lockdown, may have carried the deepest scars. She was in Upper Sixth when school closed overnight. Her rich social world vanished. School became a laptop on her duvet. Her older sister was away at university, and she was isolated from her friends. Her Leavers’ Day, a rite of passage she had anticipated for years, was reduced to a patchwork video of five-second clips. A digital imitation of something irreplaceable.

University in Dublin was worse. She lived under conditions that were genuinely dystopian: first-years confined to their tiny apartment groups, forbidden to visit friends even across the corridor. Second-year students were paying reduced rent to monitor them, knock on doors, and report any ‘breaches’. These students were paying reduced rent in order to incentivise them to ‘catch’ as meant first years breaking the ‘rules’; as many as possible. Fines of between €50 and €250 were issued for basic human contact; a perverse little economy of punishment.

She pushed through until February, then finally moved off campus with a friend just to breathe like a human being. A few weeks later, she invited a handful of friends over, not a wild party, just company, snacks, normal teenage life. Two men knocked on the window, thinking they were students, and she told them to come to the door. They were plainclothes police. They berated the girls, told them their parents would be ashamed, accused them of endangering their grandparents, and issued each of them a €1000 fine. She was 17 years old, far from home, and she has never fully recovered her confidence since.

Even as campus restrictions eased later that year, the reality barely changed: lectures stayed online, events cancelled, no balls, no parties, no trips. Her entire first year was shaped by anxiety, shame, guilt, and the sense of being constantly watched. Now she looks back and says, ‘Well, we got through it’’.

Each of my five children was marked deeply by policies that achieved absolutely nothing.

The cost was enormous. The benefits were non-existent. And as their mother, I can say without hesitation, I can never forgive it, and I will never forget it.

The Daily Mail quoted Dorette:

The exceptional circumstances threw them into total dependency. As she says: ‘We didn’t spend a minute apart.’ She admitted that when her son started reception, he could not take his coat or shoes off by himself. I had no way of checking her child’s milestones or discovering the level of development expected by his school when he started.

The same article said:

Candice, meanwhile, was locked down on her own with a newborn and a one-year-old on the fourth floor of a house with no lift in Croydon, South London. She recalled one afternoon of good weather. She managed to get both children and the buggy down the four floors and out into a nearby park. She was sitting on a bench, enjoying the sunshine and breastfeeding her baby, when a policeman moved her on. ‘I didn’t go out after that,’ she said.

The excellent Dr Sidley, writing in HART’s Substack, puts more faces to the data, and indeed, with a similar title to this series: ‘Let’s Not Forget’.

- “My teenage daughter and her friends think lockdowns will never end and are starting to wonder what the point of anything is. We have been talking about her thoughts of suicide. I’m terrified”. (Parent during lockdown)

- “My four-year-old son is hysterical. He’s in tears for the third time today, trying to engage with online teaching”. (Parent during lockdown)

- “My [younger] sisters’ schools are still closed, as well. They haven’t seen the inside of a classroom for a year, and ‘remote learning’ is nothing short of torture for little kids who need movement, play and interaction”. (Olivier, 19-year-old college student).

Dr Sidley also wrote about:

all the babies/toddlers who were starved of human contact and suffered speech impairments, cognitive deficits, and reduced motor performance; the millions of infants and teenagers across the world whose education was suspended, and life chances diminished; and the 100,000 UK children who never returned to school after lockdown …

Also, according to Dr Sidley:

lockdowns were centrally culpable for a torrent of suffering and despair, and spare a thought for: all those who were tormented with anxiety and depression; the swathes of children and young people whose mental health deteriorated; the kids admitted to hospital with eating disorders; those whose solitude tipped them over into psychosis; and the hopeless souls tormented with suicidal thoughts and driven to drug overdoses and self-annihilation.

The emotional reality is clear in these statements: suicidal thoughts, being tortured, crying, fear, anxiety, depression, lack of independence, and pain.

Many parents, such as Sally, tried to deal with the school authorities. Parents knew that their children were not at risk from Covid, nor a risk to anyone else. The stress and frustration of the situation radiates with many parents, arguing that schools fail to appreciate how lockdowns changed the dynamic between parents and children.

So, the logic behind Government policies, namely that the children were at risk and a risk to others, was totally flawed. Furthermore, the Government had all the data and evidence necessary to avoid the hugely damaging policies. There was no need for school closures, nor any of the restrictive measures which so damaged our children. Children were not at risk; they posed no risk to anyone else. Lockdowns and school closures were unnecessary and, in any case, do not work.

Yet, no one has been held accountable for the damage cased to a generation of children and young people.

Why?