The English common law rests upon a bargain between the Law and the People. The jury box is where people come into the court; the judge watches them and the jury watches back. A jury is the place where the bargain is struck. The jury attends in judgment, not only upon the accused, but also upon the justice and humanity of the law.

E.P. Thompson’s analysis, from his 1980 book Writing by Candlelight, is — quite rightly — oft-quoted. However, the English common law continues to take a battering far more harsh than any ‘named storm’ may deliver, at the hands of all three branches of government. Common law is variously labelled as out of date or, worse still, ‘abolished’ and ‘replaced’ by statute. Incongruously, it is so-called ‘Parliamentary Sovereignty’ which allows for such abuses.

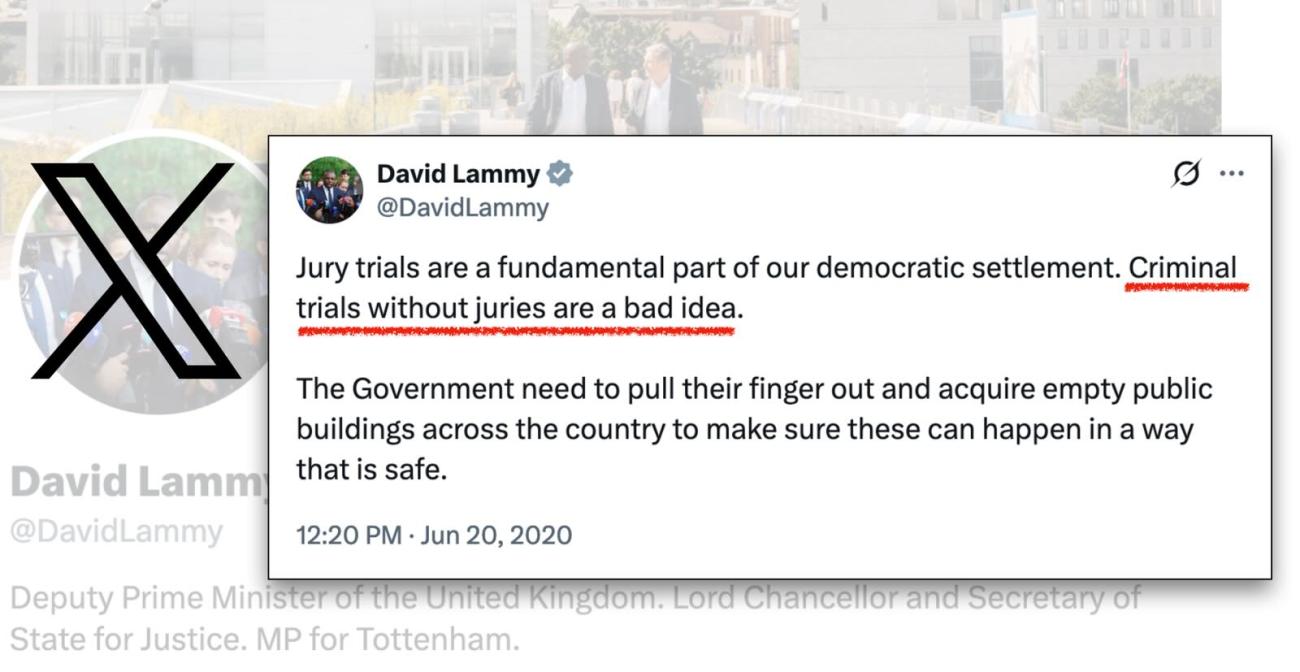

With the jury as the target, David Lammy and Lord Leveson are found sharpening their spears. The focus of the attack, so far, has been on the very existence of juries, via the introduction of several ‘time-saving’ schemes reducing the situations in which trial by jury would take place. The element so obviously missing from this campaign is, ironically, honesty. In short, the arguments that jury trials take ‘too long’ and ‘clog the system’ are guff, which will be substantiated later. An absolutely critical sidenote to this latest skirmish is that doing away with juries — wholesale or piecemeal — would consign the ability of the jury to acquit based on conscience to the wastepaper basket of history. It is to this that Thompson refers with his clause on the ‘justice and humanity of the law’, or 'jury nullification' in common parlance.

Now, in a twist that Joseph Heller would have been proud of, merely reading this may eliminate you from jury service in the United Kingdom. For a jury to return a ‘perverse verdict’ is a direct breach of the oath sworn by jurors: “I swear by Almighty God that I will faithfully try the defendant and give a true verdict according to the evidence”. Words are not minced in the Government’s aide-mémoire for jurors, which states that “the fairness of the trial depends on you following a few very IMPORTANT LEGAL RULES [emphasis in original]” and goes on to dangle the threat of “prison, a fine or both” if you step out of line. Among the many things missing from this animated document is the fact that a jury may acquit, in spite of direction of a judge to do the opposite and in spite of the “evidence you hear in court” and — most importantly — that such an action may not be overturned.

Scaremongering, so often the instrument first selected by the Government, obscures the truth for jurors. Whilst it may be the case that a failure to fulfil their sworn duties during the trial could land a jury in hot water, they cannot be found in contempt when defying the direction of the judge. This is not to say that there have never been consequences for such defiance, the most notable of which were seen in ‘Bushell’s Case’. In 1670, the refusal of a jury to comply with the direction of the judge in the case against Penn and Mead was met with harsh consequences. As the two men were tried with preaching to what was characterised an “unlawful assembly” in the City of London, the recalcitrant jury (led by Bushell) was — for three whole days — denied “‘meat, drink, fire and tobacco,’ or ‘so much as a chamber pot, if desired’”, in order that they toe the line. Notably, they refused, and created a poignant piece of history, as well-explained by The Justice Gap. When submitting written evidence to Parliament in 2025, Ray Brown made explicit reference to this historic example, and reminded the judiciary that “that the jury is not an extension of the state but an essential counterbalance to its power”.

It is the case, then, that a jury may acquit, even in circumstances where both the evidence and the direction of the judge point towards a conviction, and there are recent examples of exactly this. The rub lies in the awareness of the jury that such an outcome is possible, as it is argued that this knowledge would “prejudice the fairness” of the trial. In his Review of the Criminal Courts of England and Wales in 2001, Lord Justice Auld conceded the ability of a jury to nullify, but was adamant that “they have no right to do so”, a view shared by the majority of his profession. The common law tenet of double jeopardy used to preclude an acquitted party from being tried, again, for the same thing. In another example of modern meddling, Part 10 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (the 2003 Act) reforms the law relating to double jeopardy by “permitting retrials in respect of a number of very serious offences, where new and compelling evidence has come to light.” In other words, the state is afforded another bite of the cherry, which — just like jury nullification — may be said to cut both ways.

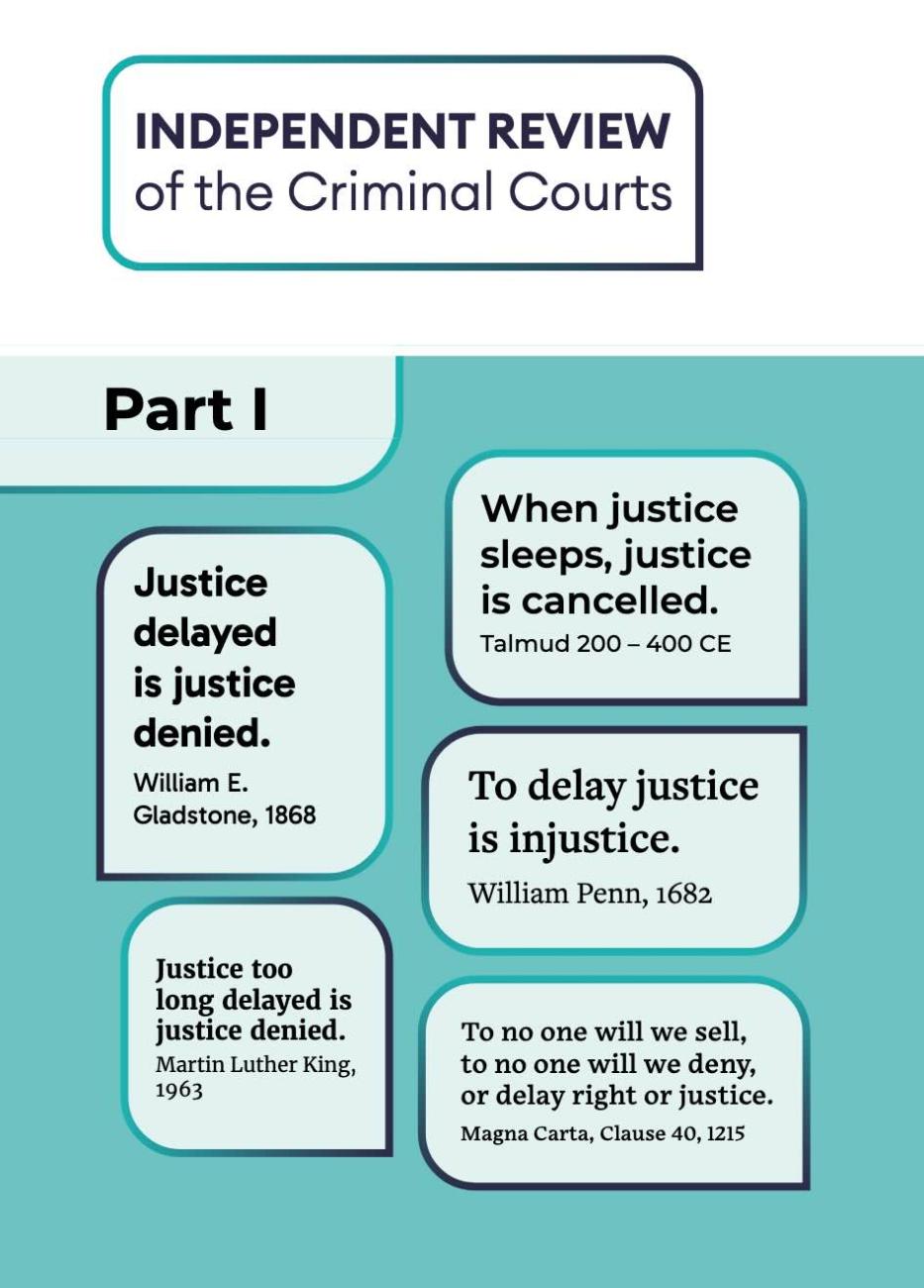

To return to the question of honesty, the Government’s attitude to cake needs examination. Bounteous evidence of a desire to both have it and eat it throws up the sticky issue of the origins of trial by jury. As it stands, the Government implies cleaving to the ‘remaining’ four clauses of Magna Carta 1215, whilst simultaneously backing judicial reform intent on discrediting one of them in particular. The front cover of Part 1 of the Independent Review of the Criminal Courts is awash with selective quotes that prioritise timeliness over fairness (including from The Talmud), and clause 40 of Magna Carta is one of them: “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny, or delay right or justice”. Indeed, and hasn’t David Lammy made much of it? Arguably, the preceding clause packs more of a punch: “No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled or ruined in any way, nor in any way proceeded against, except by the lawful judgement of his peers and the law of the land.” The Government may be regarded as consistent, in that it upholds no part of clause 39, despite suggesting that these “clauses remain law today, and provided the basis for important principles in English law developed in the fourteenth through to the seventeenth century”.

The fact that trial by jury is not mentioned in explicit terms by Magna Carta is exploited mercilessly. Auld was onto it a two and half decades ago: “Magna Carta is no basis for jury trial as we know it today”. How the irony bites when one considers that a report on reform and development is so intransigent on this particular point. Aligned with the chronology, the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary tells us that the “seeds of the modern justice system were sown by Henry II (1154-1189), who established a jury of 12 local knights to settle disputes over the ownership of land”. When it comes to “judgement of his peers”, though, no seeds. This is a grotesque inconsistency, and one much reinforced recently. Leveson gold plates the sentiment of the previous reviewer: “In short, no right to jury can be derived from Magna Carta”. Not only is this disingenuous, it infers that by knocking down the 1215 claim, there may be no other legitimacy afforded to the established practice of trial by jury.

Sarah Sackman KC MP, the Minister for Courts and Legal Services, was quick to parrot Auld and Leveson during the parliamentary debate triggered by David Lammy’s proclamations. She said that “There is no right in our constitution to a jury trial” and, instead, shifted the focus to speed, by invoking Lammy’s repeated refrain: “justice delayed is justice denied”. True enough, but this is not the whole picture, and context is everything. 2024 figures from the House of Commons Library Court Statistics for England and Wales give a figure of around 1.4 million criminal court cases per annum, with around 90% of those going via the Magistrates Courts. This is a lot; during the past five years, the Supreme People’s Court in China has run fewer cases. There can be no suggestion that this statistical comparison is like for like, but with an average of only 1.05 million per year in China, it is reasonable to ask whether the UK is actually full of lawless individuals, or has the criminal justice system taken its zeal to a new level? To extrapolate and oversimplify, the total UK cases equate to 2% of the whole population, and the total China cases equate to just 0.075% of the population.

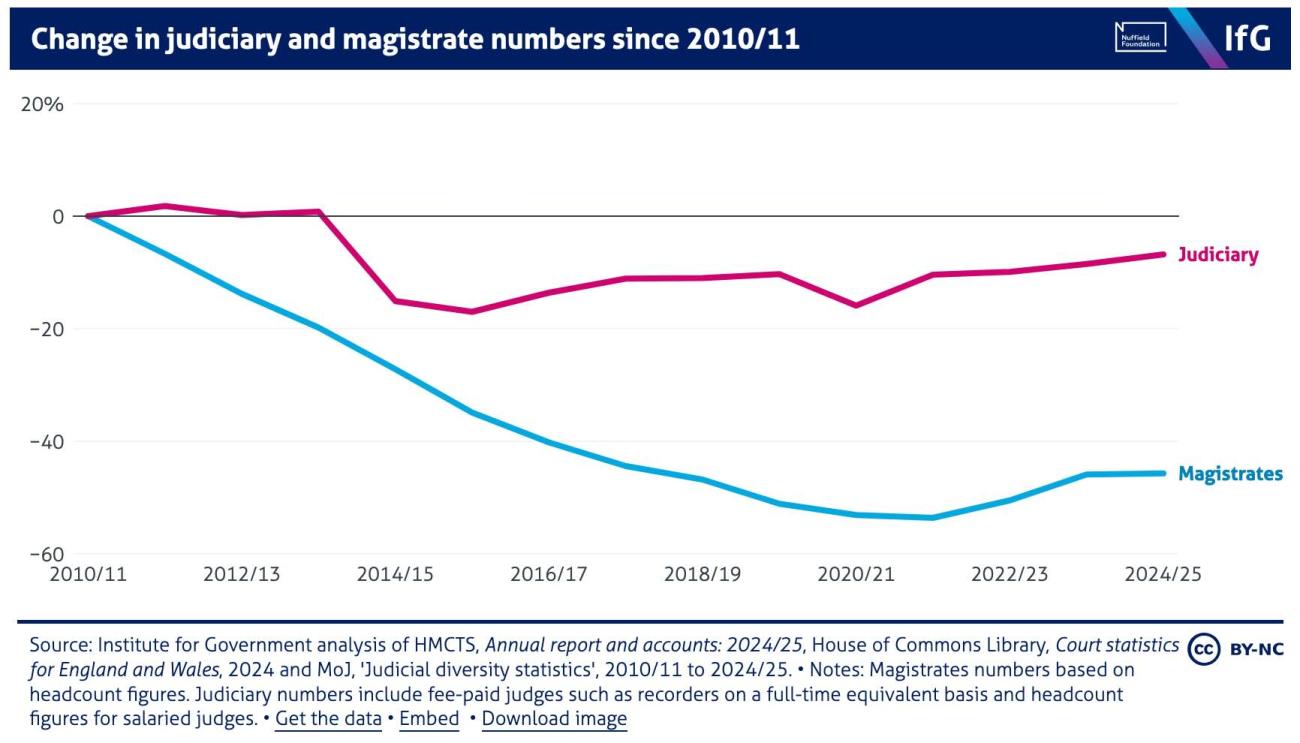

The justification for the reduction of trial by jury — that of timeliness — is a manufactured backlog, as made very clear by the Institute for Government’s Performance Tracker 2025:

The central reason why court activity remains lower than in 2016 is a substantial drop in productivity, in both magistrates’ courts and the crown court. More time is wasted in and around courts, so the increase in court funding and sitting days is not translating to a commensurate increase in capacity.

The damning does not end there. The critical finding is that:

If these problems can be adequately addressed, many of the proposals for radical reform in the courts – such as Sir Brian Leveson’s suggested restrictions on jury trials – would not be necessary.

There is more than an oblique connection to jury nullification here. If the prevailing view of the executive and the judiciary is that a judge knows better than a jury, how does that square with the proposed alternative? Leveson writes that “Confidence in the ability of the magistrates’ court to make decisions is paramount to supporting the implementation of these options and the general objectives of this Review”. Even if it is the case that 90% of criminal cases are decided by magistrates, from whence does he divine such confidence in their decision-making ability? The reason this question must be asked is that to become a magistrate, you “do not need formal qualifications or legal training.” Not only that, but “In the first 2 years, you will have about 10 days of training”. The suggestion that a magistrate may act as a check or counterbalance to a judge in Leveson’s ‘Crown Court (Bench Division)’ recommendation is laughable. Instead, underqualified and undertrained court wallahs would fall into line. It is already Leveson’s view that the job of a jury is to act “in compliance with the judge’s directions” and, in recognition of the possibility that this may not always turn out right, he proposes a more surefire method.

Then there are the practical details which further deflate the ‘time’ narrative. The most important one of these is that there are too few magistrates out there, as the IfG makes clear. Again, on time, no thought is given to the possibility that a lot of magistrates’ convictions are rushed and unsafe, as defendants “are dealt with very quickly, with many cases decided in less than a minute.” Justice denied?

In 2025, the Leveson Review recommended a serious blow to the foundations of the inherent fairness of a trial by further restricting the part juries may play in the delivery of justice. In 2001, Auld recommended that “the law should be declared, by statute if need be, that juries have no right to acquit defendants in defiance of the law or in disregard of the evidence, and that judges and advocates should conduct criminal cases accordingly.” Books have been cooked and history tampered with, but the view would not be complete without a glance at how a ‘perverse verdict’ may play out.

In 2020, the so-called Colston Four flipped a statue of Edward Colston — merchant, Member of Parliament, and member of the Royal African Company — into the harbour at Bristol. They were later tried for criminal damage. Despite the incontrovertible evidence that criminal damage had been committed by each of the four defendants, the jury acquitted them in stark defiance of the judge’s direction. As articulated in the judgement, several defences were offered, including one based on the charge of criminal damage being disproportionate to the infringement of the right to protest. Since the jury need not explain its decision, the reason for the acquittal was not clear to the court. What was clear, though, was the strenuousness of the then-Attorney General’s attempt to interfere with the process. Suella Braverman QC MP wrote that “The Court of Appeal will be asked to clarify the law around whether someone can use a defence related to their human rights when they are accused of criminal damage”; the very confluence of the threat to both trial by jury and the right to protest.

As this issue of The Blindfold Briefing goes to print, a situation unfolds which articulates the very essence of this debate. Rajiv Menon KC, a defence barrister in the trial of the ‘Filton 6’, has just reminded the jury:

His Lordship is not directing you to convict. In fact, not only is he not directing you to convict, but he’s also absolutely forbidden from doing so as a matter of law. The law is crystal clear on this point. No judge in any criminal case is allowed to direct a jury to convict any defendant of any criminal charge, whatever the evidence might be. That is the law.

A judge may direct a jury towards acquittal, and R v Wang 2005 caused the Appellate Committee to deliberate on the overstepping of Judge Pearson, who had told the jury: "As a matter of law, however, the offences themselves are proved and, under those circumstances, I direct that you return guilty verdicts on each of the two counts on this indictment." The Committee dealt with this question: "In what circumstances, if any, is a judge entitled to direct a jury to return a verdict of guilty?" According to Menon, the answer is never, so it is most telling that “The Crown contests that view, while acknowledging that the circumstances in which such a direction may be given are rare and exceptional”.

The situation has moved on apace since Malcolm Massey wrote for UK Column on this subject back in 2012. The Establishment’s continued assault on the people is, perhaps, no better exemplified by the orchestration of this campaign against trial by jury and the jurors themselves. To what extent will Bushell’s flame be rekindled?

Main image: Magna Carta. King John signing the Magna Carta reluctantly by Michael, Arthur C (d 1945)