How has a territory 50 times larger than Denmark, but with a population equivalent to a quarter of Aberdeen City in Scotland, still avoided annexation by a major power?

Upon sober geostrategic analysis, it is remarkable that the small state of Denmark's absurdly asymmetric historical claim to the landmass has been respected for so long.

One reason appears to be the climate; the enormous landmass is 80% covered by ice.

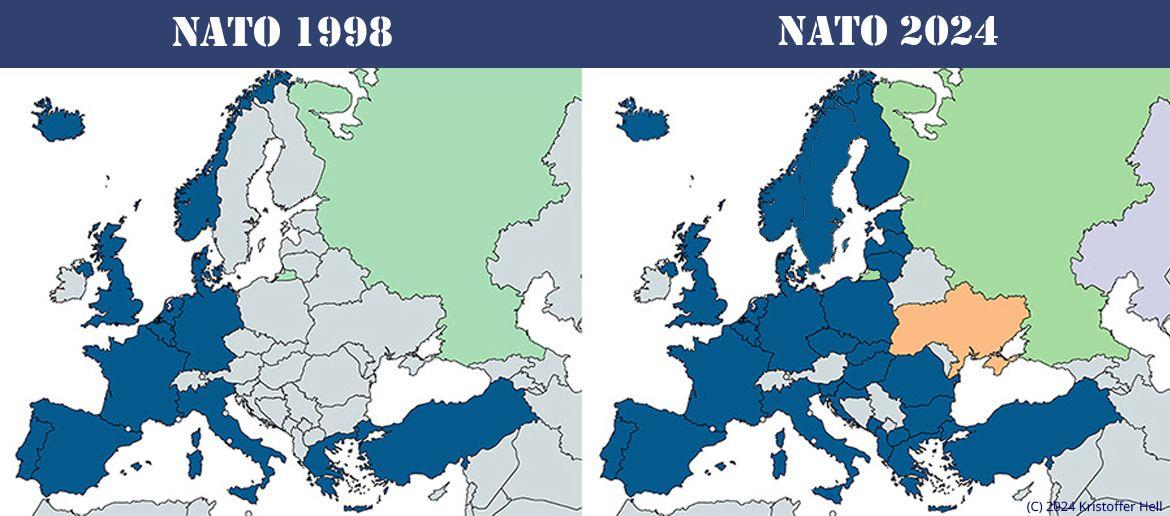

Another reason is good and close cooperation within the NATO defence alliance. This cooperation has, however, undergone major changes.

NATO

After the end of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the West, NATO was given a new mission in 1999: to transition into a military alliance aimed at eastward expansion and out-of-area operations.

When the US recently realised that the project had hit a wall and that the West's proxy war in Ukraine against the Russian Federation had collapsed, Washington evidently decided to abandon NATO and instead focus on American territorial expansion: ‘Make America Great Again’.

Geography

A glance at the map shows that Canada and the USA are geographically more natural owners of the world's largest island.

The current holder, Denmark, is a small European state with its settlements situated on a coastal strip at the entrance from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea, 3,000 kilometres away — nearly six hours' flight time.

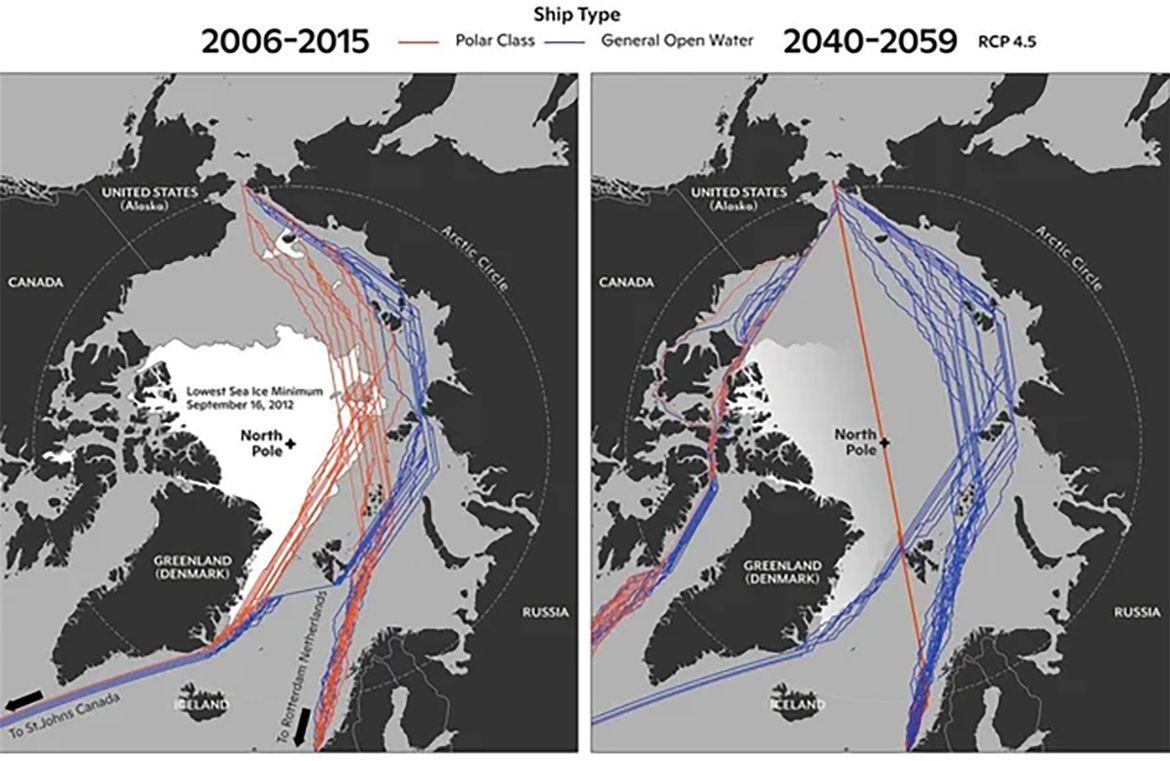

Graphics from the American NOAA (2022) show Arctic sea routes expected to become accessible to regular vessels (blue) and icebreakers (red) around Greenland in the coming decades.

The Danish Alternative

Denmark's colonisation of Greenland began in 1721 with the Danish-Norwegian missionary Hans Egede's establishment of a settlement on the island. This event marked the start of over three centuries of Danish colonial rule. During this period, Greenlanders — primarily Inuit — faced systematic marginalisation and cultural suppression. One of the darkest chapters occurred between the 1960s and the early 1990s when Danish authorities subjected Inuit women and girls in Greenland to enforced contraception, including IUD insertions and hormonal methods, often causing long-term reproductive harm such as infertility. The program effectively ended around 1991, shortly before Greenland assumed responsibility for its own healthcare in 1992.

In 1979, Greenland gained home rule, followed 30 years later by self-government in 2009. In 2022, Denmark finally issued an official apology for the medical abuses.

Today, Greenland holds the status of an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, with Copenhagen retaining control over foreign affairs, defence, and monetary policy. Even before President Trump articulated a desire to purchase the island, an internal Greenlandic debate about full independence was already underway.

Could it be that the only way the US would not see a need to assimilate Greenland is if Denmark first rolls back all the freedoms granted and progress made in Greenland since 1979 and turns Greenland into the new Denmark, relocating at least half the Danish population, the capital, political life, and industries to the island, thereby demonstrating to the world 100% seriousness regarding Greenland's future and security?

Anything else risks being perceived as European post-colonial whining.

But would the indigenous Inuit population accept such a solution — to be once again assimilated by a European Lilliputian state with a history of over three hundred years of colonial oppression? Perhaps thoughts are circulating amongst the Inuit population that together with the US, they would be materially far better off?

Will Denmark and the rest of Europe give up their claim to the Inuit homeland, accept that NATO has died, and bury the hatchet with Russia — and instead use the inevitable geostrategic shift to chart a new course and, together with Moscow, transform Europe into a constructive world leader?

Or will the decision taken in Copenhagen be to invest even more in conflict and war, dragging Europe ever deeper into a democratic, political and economic quagmire?

Cover image: Kristoffer Hell