Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of murder and mystery, and his hauntingly beautiful poems, have fascinated readers for nearly two centuries. From the 'Tell-Tale Heart' and 'The Purloined Letter' to 'Annabel Lee' and 'The Raven', Poe’s works have left an indelible mark on the world of arts and letters. With countless translations of his work into languages across the world, adaptations in films, cartoons, and Poe-inspired art of every kind, his works continue to captivate the imagination of new generations.

Art and literature have never forgotten what the great artist gave us. And yet, the sublime works he left us have been unfortunately treated as the creations of a dark mind plagued by fascinations with morbidity and all things macabre. Today, it’s commonly believed even by some of the most die-hard fans that Poe’s essential genius lay in his ability to externalize the haunting phantasms of his own tormented psyche.

Indeed, many believe that great creativity is itself often merely the beautiful byproduct of a sick mind. But is there really any evidence to support these claims, particularly in the case of a genius like Edgar Allan Poe?

As this article will demonstrate, rather than a master of the macabre, Poe would better understood as a master of the sublime. This fresh view of Poe and his work has major implications for the world of arts and letters. With a proper reassessment of Poe’s creative legacy, the sublime may once again triumph over the perverse and the grotesque in the world of art.

But to even entertain this idea, we must first attempt an even more daring enterprise: solving what may be one of the most heinous double murders in the history of arts and letters — the murder of Edgar Allan Poe himself — first in body and then in character.

And this is where our tale begins.

A Double Murder?

The common portrayal of Poe as an artist whose stories were simply the product of his own sick mind stems from the demonstrably false accounts and characterizations promulgated by Poe’s own arch-nemesis, Rufus Griswold. Griswold, who was a popular literary critic during Poe’s lifetime, painted the portrait of a self-destructive genius with no moral tiller and an obsession with worldly fame.

In his eulogy, Griswold made the following choice remarks days after Poe’s death:

… Passion, in him, comprehended many of the worst emotions which militate against human happiness. You could not contradict him, but you raised quick choler; you could not speak of wealth, but his cheek paled with gnawing envy. The astonishing natural advantages of this poor boy — his beauty, his readiness, the daring spirit that breathed around him like a fiery atmosphere — had raised his constitutional self-confidence into an arrogance that turned his very claims to admiration into prejudices against him. Irascible, envious — bad enough, but not the worst, for these salient angles were all varnished over with a cold, repellant cynicism, in his passions vented themselves in sneers. There seemed to him no moral susceptibility; and, what was more remarkable in a proud nature, little or nothing of the true point of honor.

Griswold would go on to acquire all of Poe’s letters and manuscripts from his impoverished aunt, making him the de facto narrative controller and executor of Poe’s literary estate.

Although he admired him, the famous French poet and Poe translator Charles Baudelaire propagated some equally perverse myths about the author. He was persuaded that Poe used mind-altering substances to achieve the dark states of enchantment that supposedly made his stories possible.

Baudelaire wrote in Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Works:

I believe that, in many cases, not certainly in all, the intoxication of Poe was a mnemonic means, a method of work, a method energetic and fatal, but appropriate to his passionate nature. The poet had learned to drink as a laborious author exercises himself in filling note-books. He could not resist the desire of finding again those visions, marvellous or awful — those subtle conceptions which he had met before in a preceding tempest; they were old acquaintances which imperatively attracted him, and to renew his knowledge of them, he took a road most dangerous, but most direct. The works that give us so much pleasure to-day were, in reality, the cause of his death.

As is often the case, Baudelaire's analysis sounds more like a textbook case of projection, given he was himself an unabashed hedonist and dissolute who loved to experiment with drugs, including opium and hashish, among other things.

In Poe’s case, however, the only people presumably using opium were the deranged characters in his stories like 'Ligeia' or 'Berenice'. But the sick-minded villains and madmen in his stories almost always get what’s coming to them, and they seldom escape their conscience without dire consequences. Time and time again, Poe’s tales harken back to the principle embodied by the Classical Greek goddess Nemesis, the goddess of justice and vengeance. Nemesis always gets retribution on behalf of the gods for acts of great hubris and violence against the innocent.

A higher system of law always prevails.

So the perpetrator of the heinous deeds in 'The Tell-Tale Heart' cannot help but hear the beating of a heart — supposedly the still-beating heart of the dead old man he’s carefully hidden under the floorboards. After reports of a terrifying shriek in the middle of the night, officers arrive at the old man’s house to inspect. Although at first confident that the body is well-hidden, the murderer finds himself unable to quiet the strange pulsing sound in his head. Finally, the murderer does himself in and reveals the body to officers in a desperate attempt to quell the sound of the old man’s heart.

In 'The Fall of the House of Usher', the benighted blue-blooded oligarch Roderich Usher laments the twilight of his once-glorious high bloodline. Unable to grapple with the reality of a changing world that has shrugged off the old order — symbolised by the young American Republic’s embrace of progress and optimism — the House of Usher must inevitably fall to ruin. Roderick ultimately sinks with the crumbling castle, with both him and his creepy sister locked inside.

In one tale after another, we find new variations on the same essential theme, which was symbolised for the Classical Greeks by the divine — and often terrifying — vengeance of the goddess Nemesis. And yet, despite the horror which portrayals of such justice entail, audiences consistently find themselves moved by a kind of riveting delight, which the poet Friedrich Schiller defined as the feeling of the sublime.

In On the Sublime, Schiller describes the feeling as follows:

The feeling of the sublime is a mixed feeling. It is a combination of woefulness, which expresses itself in its highest degree as a shudder, and of joyfulness, which can rise up to enrapture, and, although it is not properly pleasure, is yet widely preferred to every pleasure by fine souls. This union of two contradictory sentiments in a single feeling proves our moral independence in an irrefutable manner. For as it is absolutely impossible that the same object stand in two opposite relations to us, so does it follow therefrom, that we ourselves stand in two different relations to the object, so that consequently two opposite natures must be united in us, which are interested in the conception of the same in completely opposite ways. We therefore experience through the feeling of the sublime, that the state of our mind does not necessarily conform to the state of the senses, that the laws of nature are not necessarily also those of ours, and that we have in us an independent principle, which is independent of all sensuous emotions.

It’s notable that Schiller himself treated the theme of Nemesis in his famous poem 'The Cranes of Ibykus'. Poe also inscribed Schiller’s poem 'The Greatness of the World' on the flyleaf of his own personal copy of his prose poem 'Eureka', suggesting Poe was well-acquainted with the theme and may have drawn inspiration from Schiller’s own treatment of Classical Greek themes.

While the principle of the sublime doesn’t easily lend itself to description, we as limited beings in both perception and discernment on occasion find ourselves in moments where we catch a glimpse of a higher system of law. While invisible to us in everyday life, something is awakened deep within us when this system makes itself known. A consciousness of this principle within us confirms that we too are a part of a higher system of law. There is an 'independent principle' within us, a sixth sense stirred by things like justice and the sublime. As Schiller reminds us, this delight, “although it is not properly pleasure, is yet widely preferred to every pleasure by fine souls”.

Now, add to the gross misinterpretations of Poe’s works, the coordinated character assassination and the creation of a national Poe mythology, and then hold in mind the suspicious circumstances surrounding his own death. According to the official story, Poe was found delirious, outside a tavern, wearing someone else’s ill-fitting clothes. While no official explanation exists, the preferred theory is that Poe was a victim of political 'cooping' operations in Baltimore. 'Cooping' was an election meddling practice where citizens were kidnapped, liquored up, and forced to vote multiple times (using different disguises). It is the preferred theory for many critics simply because it seems the likeliest, so we are told, given the supposed prevalence of the practice in the Baltimore area.

The reasoning underlying this theory becomes more relevant once we revisit Poe’s own tales of murder and mystery. For instance, while adapted as a work of fiction, 'The Mystery of Marie Roget' was based on a real-life murder that sparked the first nation-wide media frenzy surrounding the murder of a young woman. Poe had taken it upon himself to solve the mystery with one of his own 'fictional' tales.

The mystery of Poe’s death becomes even more interesting once we consider his family connections to American wartime intelligence through his grandfather, David Poe, and the literary salon circles Poe frequented in his lifetime. These circles included authors like James Fenimore Cooper (author of The Spy) and Washington Irving (author of Sleepy Hollow and a US ambassador to Spain). These subjects are explored in detail for the first time in the new full-length documentary Edgar Allan Poe’s Final Mystery.

The Art of Ratiocination

Is it possible to use Poe’s own fictional stories to unearth his true identity and potentially solve the mystery of his own murder? A closer reading of his works, especially his detective tales, suggests that may finally be possible.

Whether the mystery pertains to an unsolved crime, a mysterious figure, an enigmatic work of art, or a scientific paradox, many of Poe’s most important pieces were dedicated to placing his readers in the mental disposition that allows men to venture beyond their usual blind reliance on sense-experience or their common adherence to unchallenged assumptions and authority. Instead, Poe’s philosophy of analysis is rooted in the tradition he associates with great scientific discoveries. He describes how a proper method of inquiry must necessarily defy the standard academic approach that assumes only two fundamental paths to truth exist: a priori deductive and a posteriori inductive methods.

In his metaphysical prose poem 'Eureka', Poe writes: “You can easily understand how restrictions so absurd on their very face must have operated, in those days, to retard the progress of true Science, which makes its most important advances — as all History will show — by seemingly intuitive leaps”.

These “seemingly intuitive leaps” are the subject of his famous detective stories.

The Purloined Letter

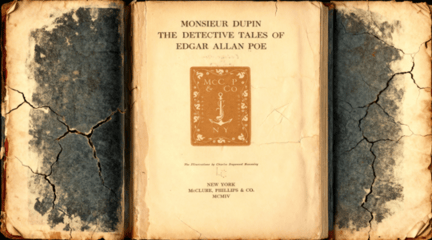

In ‘The Purloined Letter’, the third of Poe’s three famous ‘Tales of Ratiocination’, the character Inspector C. Auguste Dupin embodies the highest calibre of creative, healthy mind, which he contrasts with the French prefect and an armada of police officers who are locked in the invisible cage of sterile deductive/inductive logic. As a result, they are incapable of calling into question any of their basic assumptions or the limits of their methodology as they carry out their investigation.

An exasperated French prefect seeks the assistance of Dupin after weeks of painstakingly searching the home of a figure who is the prime suspect in the theft of a letter which holds vast political ramifications (and vast rewards if it is recovered). The inspector describes in agonizing detail how his officers have spent weeks taking apart every segment of the suspect’s home in search of the letter, but to no avail.

The Prefect describes how his men have investigated every square inch of the residence:

We took our time. First, we examined the furniture in every room. We opened all the drawers. We looked under the rugs. We searched behind all the paintings on the walls. We opened every book. We removed the boards of the floor. We even took the tops off the tables to see if he had hidden the letter in the table legs. But we cannot find it. What do you advise me to do?

Every technique of inquiry known to them has been exhausted, and their failure causes them to seek Dupin’s help.

After several days, Dupin uncovers the letter and gives it to the Prefect, who giddily pays Dupin the generous reward, leaving the inspector’s home, letter in hand. Dupin’s friend (and the story’s narrator) sits awestruck as to how this feat occurred. Dupin then explains how he was able to accomplish this seemingly impossible task by first sharing his insight into the failures of the thinking of the Prefect and officers:

The Prefect and his cohort fail so frequently, first, by default of this identification, and, secondly, by ill-admeasurement … of the intellect with which they are engaged. They consider only their own ideas of ingenuity; and, in searching for anything hidden, advert only to the modes in which they would have hidden it. They are right in this much — that their own ingenuity is a faithful representative of that of the mass; but when the cunning of the individual felon is diverse in character from their own, the felon foils them, of course. This always happens when it is above their own, and very usually when it is below. They have no variation of principle in their investigations; at best, when urged by some unusual emergency — by some extraordinary reward — they extend or exaggerate their old modes of practice, without touching their principles.

Dupin reveals that the stolen letter was hidden in plain sight, smeared with some lipstick and crunched up in a ball sitting in open view upon a desk. Visible to all eyes, but invisible to all defective minds obsessed with deductive analysis.

Dupin elaborates on the superiority of the culprit’s creative mind, saying: “I know him well; he is both. As poet and mathematician, he would reason well; as mere mathematician, he could not have reasoned at all, and thus would have been at the mercy of the Prefect”.

It was Dupin’s insight into the failure of linear mathematical logic and the healthy maturation of scientific and aesthetic capacities that true creative leaps into discovery concepts occur. They are never the product of some formula.

Since the time of his stories, everyone from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie to major Hollywood screenwriters have imitated the genre uniquely created by Poe. But unlike many of the imitations, which usually lack Poe’s rigorous methodology, Poe’s tales may allow us to solve real crimes today — including the mystery of his own death.

And that leads us to one of Poe’s most famous tales.

The Murder of Marie Roget

As already noted, Poe’s tale ‘The Mystery of Marie Roget’ (1842) was no ordinary work of fiction. Poe wrote the story as a fictional version of the real-life murder of a young “beautiful cigar girl” named Mary Cecilia Rogers. She was found brutally murdered and floating on the Hudson River in Hoboken, New Jersey. The mutilated body turned up just near the mouth of a mysterious cave named Sybil’s Cave. The manmade cave was peculiarly located on the estate of the powerful American Stephens family.

The murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers became the first sensational murder mystery of its kind in the young American republic, captivating the attention of readers everywhere. It sparked a frenzy of tabloid speculation about possible causes and motives. It also set the standard for all subsequent true crime stories and the manner in which mainstream media often treat suspicious murder cases. These include the sorts of murder cases usually explained away with theories of 'roving gangs' and 'lone wolves' — or the sorts of crimes involving signs of ritual murder (as in the case of Mary Cecilia Rogers).

In his fictional account, Poe demonstrates his method for solving the actual crime. He altered the names and locations of the original case but kept all the relevant and essential details. He substituted only inessential points that had no direct bearing on the key anomalies in the case.

The following footnote appeared in Tales by Edgar A. Poe (1845):

The ‘Mystery of Marie Rogêt’ was composed at a distance from the scene of the atrocity, and with no other means of investigation than the newspapers afforded. Thus much escaped the writer of which he could have availed himself had he been upon the spot, and visited the localities. It may not be improper to record, nevertheless, that the confessions of two persons, (one of them the Madame Deluc of the narrative) made, at different periods, long subsequent to the publication, confirmed, in full, not only the general conclusion, but absolutely all the chief hypothetical details by which that conclusion was attained.

In Poe’s tale, his detective Dupin describes in detail the obstacles preventing anyone from solving the case. The chief cause of confusion is the frenzy of mainstream media reports, which do more to obscure crucial evidence and inconsistencies than they do shine light on the unique particulars of the case.

Using the character of Inspector Dupin, Poe proffers his alternative approach to the sloppy investigative methods of the media:

In that which I now propose, we will discard the interior points of this tragedy, and concentrate our attention upon its outskirts. Not the least usual error, in investigations such as this, is the limiting of inquiry to the immediate, with total disregard of the collateral or circumstantial events. It is the mal-practice of the courts to confine evidence and discussion to the bounds of apparent relevancy. Yet experience has shown, and a true philosophy will always show, that a vast, perhaps the larger portion of truth, arises from the seemingly irrelevant. It is through the spirit of this principle, if not precisely through its letter, that modern science has resolved to calculate upon the unforeseen.

Poe’s Dupin disabuses anyone from simply relying on common knowledge or statistical probability to determine the most likely causes. Since the case is not a standard case, trying to assess which facts are relevant and which irrelevant based on the most probable situation belies the crucial details that hold the key to solving the case.

Poe’s Dupin clarifies his meaning:

But perhaps you do not comprehend me. The history of human knowledge has so uninterruptedly shown that to collateral, or incidental, or accidental events we are indebted for the most numerous and most valuable discoveries, that it has at length become necessary, in any prospective view of improvement, to make not only large, but the largest allowances for inventions that shall arise by chance, and quite out of the range of ordinary expectation. It is no longer philosophical to base, upon what has been, a vision of what is to be. Accident is admitted as a portion of the substructure. We make chance a matter of absolute calculation. We subject the unlooked for and unimagined, to the mathematical formulae of the schools.

I repeat that it is no more than fact, that the larger portion of all truth has sprung from the collateral; and it is but in accordance with the spirit of the principle involved in this fact, that I would divert inquiry, in the present case, from the trodden and hitherto unfruitful ground of the event itself, to the contemporary circumstances which surround it. While you ascertain the validity of the affidavits, I will examine the newspapers more generally than you have as yet done …

Time and time again, the tabloids make assumptions that aren’t justified by reason, only supported by the assumptions of expert opinions (who are not in the habit of revising their assumptions or methodologies). In the face of the media’s investigative incompetence, the master detective recommends ignoring the bogus analysis of the tabloids, ‘but it will be strange indeed if a comprehensive survey, such as I propose, of the public prints, will not afford us some minute points which shall establish a direction for inquiry’.

Dupin explains how while the way the tabloids frame the stories and evidence can be ignored, a survey of the particular details reported in the various presses can be useful in developing one’s own independent hypothesis.

As one example of the detective’s applied methodology, Dupin calls into question the established timeline for determining whether some of Marie’s articles of clothing found in a thicket actually confirm the scene of the crime, or its timeline:

Notwithstanding the acclamation with which the discovery of this thicket was received by the press, and the unanimity with which it was supposed to indicate the precise scene of the outrage, it must be admitted that there was some very good reason for doubt. That it was the scene, I may or I may not believe — but there was excellent reason for doubt. Had the true scene been, as Le Commerciel suggested, in the neighborhood of the Rue Pavée St. Andrée, the perpetrators of the crime, supposing them still resident in Paris, would naturally have been stricken with terror at the public attention thus acutely directed into the proper channel; and, in certain classes of minds, there would have arisen, at once, a sense of the necessity of some exertion to redivert this attention. And thus, the thicket of the Barrière du Roule having been already suspected, the idea of placing the articles where they were found, might have been naturally entertained. There is no real evidence, although Le Soleil so supposes, that the articles discovered had been more than a very few days in the thicket; while there is much circumstantial proof that they could not have remained there, without attracting attention, during the twenty days elapsing between the fatal Sunday and the afternoon upon which they were found by the boys.

Specifically, Dupin focusses on the assumed rates of mildew growth found on the shreds of Marie’s clothing:

'They were all mildewed down hard', says Le Soleil, adopting the opinions of its predecessors, 'with the action of the rain, and stuck together from mildew. The grass had grown around and over some of them. The silk of the parasol was strong, but the threads of it were run together within. The upper part, where it had been doubled and folded, was all mildewed and rotten, and tore on being opened’.

Dupin remarks on the presumed rates of mildew growth: “Is he to be told that it is one of the many classes of fungus, of which the most ordinary feature is its upspringing and decadence within twenty-four hours?”

Another instance is the experts’ presumed timeline for the murder itself, based on the decomposition of Mary’s body found floating in the Hudson River, and the timeframe for when a dead body usually sinks and later resurfaces. Poe’s Dupin then takes aim at the popular theory promulgated by the mass media, namely, that a gang of “ruffians” had to have been responsible for the murder.

Let us reflect now upon 'the traces of a struggle;' and let me ask what these traces have been supposed to demonstrate. A gang. But do they not rather demonstrate the absence of a gang? What struggle could have taken place — what struggle so violent and so enduring as to have left its 'traces' in all directions — between a weak and defenceless girl and the gang of ruffians imagined? The silent grasp of a few rough arms and all would have been over. The victim must have been absolutely passive at their will. You will here bear in mind that the arguments urged against the thicket as the scene, are applicable, in chief part, only against it as the scene of an outrage committed by more than a single individual. If we imagine but one violator, we can conceive, and thus only conceive, the struggle of so violent and so obstinate a nature as to have left the 'traces' apparent.

Since another girl had been murdered by a gang of ruffians on the same night, Marie’s murder could be assumed to have been committed by a similar type of roving gang, say the tabloids. They argue based on common sense and statistical probability, but Dupin argues that their own logic suggests the very opposite conclusion:

But, in fact, the one atrocity, known to be so committed, is, if any thing, evidence that the other, committed at a time nearly coincident, was not so committed. It would have been a miracle indeed, if, while a gang of ruffians were perpetrating, at a given locality, a most unheard-of wrong, there should have been another similar gang, in a similar locality, in the same city, under the same circumstances, with the same means and appliances, engaged in a wrong of precisely the same aspect, at precisely the same period of time! Yet in what, if not in this marvellous train of coincidence, does the accidentally suggested opinion of the populace call upon us to believe?

The very reason people believe one murder must be related to the other is nothing but lazy-minded pattern recognition. As Dupin argues, the likelihood of two simultaneous events involving the same crime committed by two separate gangs strains credulity, rather than strengthens it.

At every step, Dupin highlights the contradictions and unchecked assumptions in the major press accounts. He consistently highlights the assumptions that lead experts to believe they are simply deducing the obvious logical conclusions suggested by the evidence.

Perhaps the truth is that while the evidence may often be hidden in ‘plain sight’, that doesn’t prevent most of us from overlooking it, due to our own flawed methodologies.

Poe’s story ends with the suggestion that the boat which must have been used during the crime should be located. If investigators can find the boat, they’ll quickly find the murder.

Conclusion: Solving the Paradox of the Sublime

The great irony in our tale is that the official story of Poe’s life and death — and that of Mary Rogers — is replete with the kinds of discrepancies described in the detective tales that made Poe a household name. In the case of his death, critics suggest political ‘cooping’ is the likeliest explanation because it was an apparently popular crime during the period. A gang of political thugs kidnapped and poisoned Poe, somehow made him vote many times, and then left him for dead. The perversion of Poe’s image and works, Griswold taking over his literary estate, Poe’s deeper family ties to American Revolutionary War intelligence, and the political circles he frequented in his lifetime are all overlooked as “collateral or circumstantial events”.

Likewise, the points upon the 'outskirts' of Mary Cecilia Rogers’ own mysterious murder, including the types of wounds on her body, the peculiar location of her corpse, and her own astonishing family connections are all grossly disregarded. As already noted, the Stephens family had a strange predilection for occult real estate, including ancient Sibylline caves and ‘Elysian Fields’ — something not easily discounted by those familiar with occult symbolism and ritual. As in Poe’s own story, the systematic “disregard of the collateral or circumstantial events” becomes a natural reason for doubting the official theories in Poe’s and Mary’s cases.

Of course, these are only some among the many details and plot twists described in the new film Edgar Allan Poe’s Final Mystery: A Tale of Two Murders.

Like many who wrestle with the nature of evil, its mysterious motives and modus operandi, Poe’s method of ratiocination is an embodiment of the method of hypothesis which isn’t confined to blind reliance on sense-perception, or captive to the kinds of preconceived notions which official sources insist the public believe. This fictional method is the hallmark of every great mind capable of soaring beyond the assumptions of the commonplace — assumptions which can hamper great discoveries and stifle real progress as much as they can protect established orders and official myths.

Poe’s detective tales remind us that without a proper methodology and carefully cultivated aesthetic faculties, whose loftiest expressions are found in the intimate wedding of the poetical and scientific, getting the 'facts' mixed up is all too easy — and all too likely. Perceptions can always be manipulated or led astray — whether through the shortcomings of our own methodologies, or by design, according to the intentions and deceptions of power and media.

Minds capable of freeing themselves from these pitfalls — like Poe did in his own life and works — are usually those who become the great artists, detectives, scientists, and patriots who make the flourishing of man and the preservation of nations possible.

In conclusion, an invitation to the sublime rarely appears without the spectre of something, dark, ominous or mysterious. The kinds of dark themes and paradoxes treated by Poe in his stories—much like in a Classical Greek tragedy — are exemplary of the sublime’s strange charms. Although the feeling may initially come on as a shudder or a feeling of ‘woefulness’, on that journey we discover that however small or insignificant we may be, we are in fact the members of a higher system, and we are all on occasion called to bear it witness.

So, let us join Poe’s spirit in soaring to that long-lost abode, where justice is served and the lies against Edgar Allan Poe are repeated nevermore. Learn more about Edgar Poe’s story in the latest film about his ‘final mystery’.

Cover image: Illustration of 'The Raven' by Gustav Dore. Public Domain.